VITO ACCONCI - LANGUAGE WORKS. VIDEO, AUDIO AND POETRY

EXHIBITION

The work of Vito Acconci (b. 1940) deals with critical, now and then even playful aspects of identity politics – the ‘self’ as a social construct – and is characterised by self-motivated research into the relationship between artist and viewer, how individual and social space are related to one another. The extensive exhibition offers an insight into the practice that this influential artist carried-out in the 1970s, from the perspective of the role of language as a catalysing impulse. This is thereby the centre of gravity shaping Acconci’s conceptual, performance-based videos and audio works, wherein he executes an intense dialogue between his body and psyche, the ‘I’ and the ‘you’, the public and private space, in the form of stream-of-consciousness monologues. This historic, groundbreaking body of work, distinguished by an unusually psychodramatic intensity, is supplemented in this exhibition by graphic transcriptions of audio works and early poetry works. In these works the physical materialisation of language is central, achieved through means of syntactical experiments and typographical permutations. From the 1980s onwards Acconci’s practice shifted in the direction of sculptural interventions and urban projects, progressing his interest in the human body and its relation to the public space. Connected therewith is a surprising listening space that the artist was commissioned to design for the exhibition. A forest of hanging silver ribbons of differing lengths lifts the space up and confuses the view, so that the ‘listening’ part can override it. Under and between the masses of ribbons the visitor can freely move around on silver coloured ball seats.

The use of video as a new medium for artists, whereby Acconci qualifies as one of the absolute pioneers, also served to introduce a socio-cultural dimension into the arts in the 1970s. The physical art object cleared the terrain for divergent conceptual and process-geared practices, through which the white cube space in galleries and museums also emerged. Artists viewed video as a tool, not as a medium in itself.

And so it was with Acconci. His ‘10-point plan for video’, a mini-manifest dating from 1976, with “Video as an idea catching-on as a working method rather than as a specific medium”. If you look back on the decade it is striking to note the explanations and the reviews of artistic practice within the large modern interpretation systems. Theories coming out of the human sciences are never empty. Whereas in video, Marxism and semiology find their advocates in, for example, Martha Rosler and Gary Hill, pschoanalysis finds them in the person of Vito Acconci.

Acconci’s work is situated at the crossroads of ideas. His work method is closely allied to ‘action research’: a method in which the researcher intervenes in the topic being sought, a technique the German-American pioneer in social psychology Kurt Lewin defined in 1946 as “a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action and research leading to social action”. The ‘dramaturgic metaphor’ of the sociologist Erving Goffman – in which he compared human communication across the world and back with a theatre wherein everyone, dependent on the situation, always dressed for a different role – echoes throughout the different positions the artist adopts in his career (and, seen at a micro-level, rarely in one and the same work).

The rise of so-called ‘anti-psychiatry’ in the 1960s (a label that many mainstream researchers would reject) also strongly influenced Acconci in his thinking and activities. Above all, Ronald David Laing’s discoveries on psychosis and the importance granted to the role of the individual (i.e. the patient) inspire Acconci’s work. A quote from Laing’s standard work ‘The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness’ that appeared in 1959, gives attention, in fact, to that which Acconci’s conceptual performance practice revolves around: “The body is felt more as an object among other objects in the world than as the core of the individual’s own being." In a strict literary sense a reference can be made to William Faulkner, with his uninterrupted associative word streams, or to Samuel Beckett’s monologues.

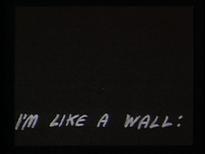

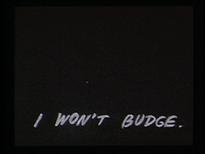

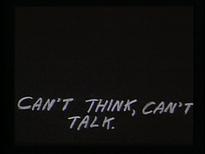

Acconci initially followed literature studies and along the way happened into the art world. In the mid-1960s, having begun as a writer and poet, he presented the white piece of paper as a container for ideas, as a place or a structure where he and the reader can freely act, can have a dialogue. In place of writing a fictive personage, Acconci impelled and influenced a real person – the recipient – in his poetry. Amongst other things, the typographic possibilities of the writing machine since having been exhausted, the page becomes a space through which the reader can navigate.

Letters, words, numbers, punctuation and white space, aim at movement, playfulness and confusion; they qualify as signposts, but also as obstacles, commandments and the forbidden. In this way Acconci uses language as a catalyst: he presents communication as a field of tension in flux whereby bonds (and disturbance factors) between sender, message and recipient, exist as an interactive process. Their problematic relationship is necessary; it forms the premise for the existence of a work. The recorded ‘Four Book’ from 1968 that is included in the exhibition, taking up, as it does, a wall of more than twenty metres, herewith serves as an illustration.

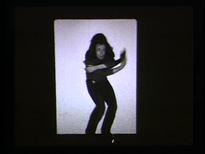

In the late 1960s Acconci widens the place on a page by applying his own body to it. The gallery, his own home, the urban and the media space, serve as laboratories for performances that he documents and analyses in sound works, photos, films and videos. His video art is directed at defining this then early medium in a manner that discusses, stretches and undermines the classic Latin meaning of the word (video for ‘I see’). Between 1969 and 1974 he realises more than 200 conceptually structured works that, however extremely simple for the most part, in terms of set-up, once again search for a direct psychological confrontation with the viewer.

Acconci plagues the viewer, holds him or her on edge, challenges them to look, to stay looking or to go away. In constantly alternating bodily positions from video to video (frontal, under, above, to the side) the artist puts himself in close-up in works such as ‘Command Performance’, ‘Theme Song’, ‘Turn on’ and ‘Face Off’. From the standpoint of the viewer he rubs himself against the screen, therewith challenging the neutrality of the medium.

The monitor as something that makes possible a one-to-one relationship with the viewer is an essential prerequisite for this work. The intimate distance and complicity that the monitor commands between artist and viewer can also be seen here as the reverse of the one-to-all scheme, the false rhetoric of the window on the world and the ideological domestication for which the mass media is responsible. With his 90-minute long magnum opus ‘The Red Tapes’ from 1977, the very last video work from this fruitful period, Acconci leaves the monitor scheme. In this epic cross-section of American culture – conceived for video projection – the close-up of the video space alternates with the landscape belonging to the film space. More than three decades later this (self-)reflective and vociferous oeuvre, slicing through modernism and post-modernism, has lost none of its force.

The use of video as a new medium for artists, whereby Acconci qualifies as one of the absolute pioneers, also served to introduce a socio-cultural dimension into the arts in the 1970s. The physical art object cleared the terrain for divergent conceptual and process-geared practices, through which the white cube space in galleries and museums also emerged. Artists viewed video as a tool, not as a medium in itself.

And so it was with Acconci. His ‘10-point plan for video’, a mini-manifest dating from 1976, with “Video as an idea catching-on as a working method rather than as a specific medium”. If you look back on the decade it is striking to note the explanations and the reviews of artistic practice within the large modern interpretation systems. Theories coming out of the human sciences are never empty. Whereas in video, Marxism and semiology find their advocates in, for example, Martha Rosler and Gary Hill, pschoanalysis finds them in the person of Vito Acconci.

Acconci’s work is situated at the crossroads of ideas. His work method is closely allied to ‘action research’: a method in which the researcher intervenes in the topic being sought, a technique the German-American pioneer in social psychology Kurt Lewin defined in 1946 as “a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action and research leading to social action”. The ‘dramaturgic metaphor’ of the sociologist Erving Goffman – in which he compared human communication across the world and back with a theatre wherein everyone, dependent on the situation, always dressed for a different role – echoes throughout the different positions the artist adopts in his career (and, seen at a micro-level, rarely in one and the same work).

The rise of so-called ‘anti-psychiatry’ in the 1960s (a label that many mainstream researchers would reject) also strongly influenced Acconci in his thinking and activities. Above all, Ronald David Laing’s discoveries on psychosis and the importance granted to the role of the individual (i.e. the patient) inspire Acconci’s work. A quote from Laing’s standard work ‘The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness’ that appeared in 1959, gives attention, in fact, to that which Acconci’s conceptual performance practice revolves around: “The body is felt more as an object among other objects in the world than as the core of the individual’s own being." In a strict literary sense a reference can be made to William Faulkner, with his uninterrupted associative word streams, or to Samuel Beckett’s monologues.

Acconci initially followed literature studies and along the way happened into the art world. In the mid-1960s, having begun as a writer and poet, he presented the white piece of paper as a container for ideas, as a place or a structure where he and the reader can freely act, can have a dialogue. In place of writing a fictive personage, Acconci impelled and influenced a real person – the recipient – in his poetry. Amongst other things, the typographic possibilities of the writing machine since having been exhausted, the page becomes a space through which the reader can navigate.

Letters, words, numbers, punctuation and white space, aim at movement, playfulness and confusion; they qualify as signposts, but also as obstacles, commandments and the forbidden. In this way Acconci uses language as a catalyst: he presents communication as a field of tension in flux whereby bonds (and disturbance factors) between sender, message and recipient, exist as an interactive process. Their problematic relationship is necessary; it forms the premise for the existence of a work. The recorded ‘Four Book’ from 1968 that is included in the exhibition, taking up, as it does, a wall of more than twenty metres, herewith serves as an illustration.

In the late 1960s Acconci widens the place on a page by applying his own body to it. The gallery, his own home, the urban and the media space, serve as laboratories for performances that he documents and analyses in sound works, photos, films and videos. His video art is directed at defining this then early medium in a manner that discusses, stretches and undermines the classic Latin meaning of the word (video for ‘I see’). Between 1969 and 1974 he realises more than 200 conceptually structured works that, however extremely simple for the most part, in terms of set-up, once again search for a direct psychological confrontation with the viewer.

Acconci plagues the viewer, holds him or her on edge, challenges them to look, to stay looking or to go away. In constantly alternating bodily positions from video to video (frontal, under, above, to the side) the artist puts himself in close-up in works such as ‘Command Performance’, ‘Theme Song’, ‘Turn on’ and ‘Face Off’. From the standpoint of the viewer he rubs himself against the screen, therewith challenging the neutrality of the medium.

The monitor as something that makes possible a one-to-one relationship with the viewer is an essential prerequisite for this work. The intimate distance and complicity that the monitor commands between artist and viewer can also be seen here as the reverse of the one-to-all scheme, the false rhetoric of the window on the world and the ideological domestication for which the mass media is responsible. With his 90-minute long magnum opus ‘The Red Tapes’ from 1977, the very last video work from this fruitful period, Acconci leaves the monitor scheme. In this epic cross-section of American culture – conceived for video projection – the close-up of the video space alternates with the landscape belonging to the film space. More than three decades later this (self-)reflective and vociferous oeuvre, slicing through modernism and post-modernism, has lost none of its force.

Gerelateerde evenementen

-

di 27.1.2009

- za 11.4.2009

-

Praktische info

Exhibition brochures are available for download:

English version

Dutch version

French version

Location:

Argos

Werfstraat 13 Rue du Chantier,

1000 Brussels

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Saturday, 12:00 to 19:00

Entrance Fee:

3 euro - Kunstenaars

- Werken