RESONATING SURFACES

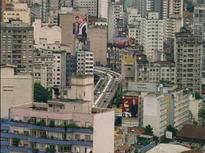

First, there’s only darkness and music combined with vague, indefinable sounds, like footsteps or stumbling. Then, slowly, the image whitens, giving way bit by bit to some 16 mm film spots and scratches. Now and then, images appear for a split second. The music swells, distorted, cut through with noise. Once the screen is completely white, we hear two female voices crying out in screams of death: scenes from Alban Berg’s operas ‘Lulu’ and ‘Wozzeck’. These women seem to scream the ends of their lives in two ways: as life that is extinguished, that disappears in the dark; and as life that continues, as a vehement cry and protest against that which threatens it. The screen goes dark again. Darkness and silence slowly give way to shots of São Paulo. First at night, then by day, the camera glides searchingly over the surface of the city. We hear soft Brazilian Portuguese words: gasoline, jasmine, café. Little by little, we get not only a portrait of a person and a city, but a story as well. It’s the story of Brazilian psychoanalyst Suely Rolnik, and the interwoven stories of dictatorship in Brazil from the 1960s to the ’80s, the Tropicalismo art movement and counterculture — and their aftermath.

Rolnik speaks about her exile in ’68 in Paris, where she hopes to find an answer to a basic question that has haunted her all through the Brazilian totalitarian experience: how to combine revolutionary politics with another way of life? How to combine politics and the personal, the sensual; how to truly live differently? In ‘Resonating Surfaces’ she says she found the answer in singing.

Thus it is no coincidence that the film starts with two women’s voices ‘singing’ their own death. Gilles Deleuze suggested them as a possible subject for a thesis she never wrote. Many years later in Brazil, they surfaced again in her doctoral study. In between, during a singing course in Paris, her own voice singing a Tropicalismo song in her Brazilian Portuguese mother tongue – “breaks through the contour of her body”. That body has by then become a white shell hardened with the help of the French language, keeping the Brazilian-induced wound protected — but intact. It is her own voice, and the Brazilian Portuguese timbre that rings in it, that makes her realise: “I want to go back to Brazil.”

Back in Brazil, Rolnik maintains contact with Deleuze and his friend and ally Félix Guattari. Deleuze, as friend and thinker, has revolutionised her life. He also serves as an organising principle for the film on a narrative and formal levels. One of Deleuze’s basic notions, namely that of difference – not as negation, but as affirmation – forms the film’s formal backbone. From the very start language and discourse (sound in general) are always presented separately from what we see. They are different realms, completing but also competing and somehow independent realities. As with de Boer’s ‘Perfect Sound – Resonating Surfaces’ is both an experiment in sound and a homage to the life-affirming forces of sound and voice. As in ‘Sylvia Kristel – Paris’, the fiction of a happy collusion between sound and image (a woman speaks; we actually see her speaking) never takes place but is replaced by ‘friction’: when we hear voices, sounds, music, no source or origin is ever revealed visually.

A dialectics between image and sound is set in motion, requiring the viewer to be in two spaces simultaneously: one aural, one visual. ‘Resonating Surfaces’ presents a ‘real’ trace of Rolnik. Still, by showing how the film is composed of edited material -- of sound (interview, soundscape, music) and filmed images -- its nature as construct and fiction is underscored. Finally, one is reminded that film is a medium that carries traces of sound and image without ever necessarily having to let them blend. (Steve Tallon)

This work has been digitised in the frame of DCA Project

- Formaat 16mm(16 mm.)

- Kleursysteem PAL

- Kleur col.

- Jaar 2005

- Duur 00:39:00

- Taalinfo

Ondertitels: English UK

Gesproken: Portuguese, French

-

Kunstenaars

-

EVENEMENTEN